Queridos amigos y familiares, July 16-17, 2006

John here. We are taking a rest day. The buzzards have been flying past our bedroom vista in twos and threes, perhaps headed to some cadaver in the jungle. The verticality of this place is such that they are mostly flying below us, even though they are flying high above the ground. For obvious reasons, we are getting plenty of exercise. Even walking to breakfast involves two flights of stairs; going downtown to the plaza is the equivalent of walking down fifteen stories, and back up them to return.

Besides difficulties of transportation, about which we have told you, the steep hillsides also define the other main aspect of this place: the cultivation of coca. Coca grows, in neat terraced rows, on the steepest grades. The plants are small and shrubby, with bright upturned leaves like immature golden privets, and the local slogan is, “coca es vida,” coca is life. The town hall even has a coca leaf on its logo, combined with a rainbow and a toucan. Small rectangular coca fields are everywhere (I could probably count thirty from our window if I looked hard at the distant opposite hillsides). But the coca production level is considerably less than it was in colonial days, when the Spanish first established haciendas in the Yungas valleys to supply coca leaves to keep their slaves working longer and harder and with less food in the famous silver mines of Potosi. Before the Spanish, the Inca royalty used coca for ceremonial purposes, and before them the ancient Aymara peoples of Tiwanaku. Some say coca has been cultivated here for several thousand years. The outlines of the old haciendas are still visible as swaths of land where the forest was once cleared, now covered in grasses that blur the faint lines of former terraces, like the wrinkles of an ancient face.

The haciendas left other legacies as well. African slaves were imported to grow the coca, and, unbelievably, these relations of master and slave persisted until Bolivia’s agrarian reform of 1952. As a result, there are many populations of Aymara and Afro-Bolivians here who have been legally tied to particular parcels of land for hundreds of years, and for whom slavery, in the full brutal meaning of the word, is a matter of vivid living memory.

This week, we spent two nights in one of these pueblos, Tocaña. This town, like all towns here, clings to a steep hillside halfway up a mountain. The inhabitants were the slave population of a hacienda until the 1950s. After the agrarian reform, the hacienda was razed, parcels were measured out for individual ownership, and the people voted to form a cooperative of growers. There are now a couple of hundred residents, almost exclusively Afro-Bolivians. They have citrus, banana, and coffee groves around their adobe houses; a church, a one-room schoolhouse for the primary grades, an African-looking cultural center financed by a European NGO; and a series of outlying coca fields stretching up, down, and to either side, dotted with swimming-pool-sized enclosures with slate floors used for drying the harvested leaves.

We arrived late Thursday hoping to tell the story of coca through this village. A Bolivian man who was trained as an anthropologist but who looks like a Rastafarian and calls himself “Pulga” is something of the town cultural interpreter. He took us under his wing, introduced us to the community leaders and local elders, and took us on a walkabout of the incredible vistas above town. After being introduced to Johnny, the leader of the growers co-op and thus effectively the mayor of the town, I asked if the people would allow us to film. He asked what the project was about, and I explained that people in the US have really no idea about the cultural and economic meaning of coca in this part of Bolivia, and that North Americans largely equate coca with cocaine. We were hoping to make a film that helped North Americans understand the difference. He said that he would ask the community.

The next morning, we saw Johnny again, and the answer was no. He explained that even though people were supportive of the idea I had expressed, because we were from the US, people suspected that our real purposes might be otherwise, and they did not want to take the risk. We told him we respected the decision and asked him if he would sit for an interview about his feelings about coca, mistrust, and the United States. He agreed. He explained that, because the people here need to grow coca to survive, and because the US wants to eradicate coca, the people basically feel that the US is trying to destroy them. Neither he nor anyone in Tocaña has any faith in the “alternative development” strategies proposed by USAID. Citrus prices are too low and coffee is too expensive to plant for more than local consumption. The land is too exhausted from centuries of cultivation to grow other things. There is no capital to retool their fields, for seeds, fertilizer, or equipment. Regional governments skim off the money that is offered for alternative development projects, so that the villages rarely get a cent. Coca, in contrast, can be harvested three times a year from the second year it is planted and sold at a decent price. And coca, simply, is life. People chew it, drink it in tea, use it medicinally, and venerate it as an offering to Pachamama, the goddess of Earth.

In 2003, the Bolivian government tried to intervene militarily in the Yungas to eradicate coca. The growers fought back with machetes, rocks, and they even threw beehives into government vehicles. The poorly-supported government force of young conscripts was besieged, defeated, repulsed. Asked if the people of Tocaña would fight again if the US tried to eradicate coca by force, Johnny shrugged, “Of course. We would have no choice.”

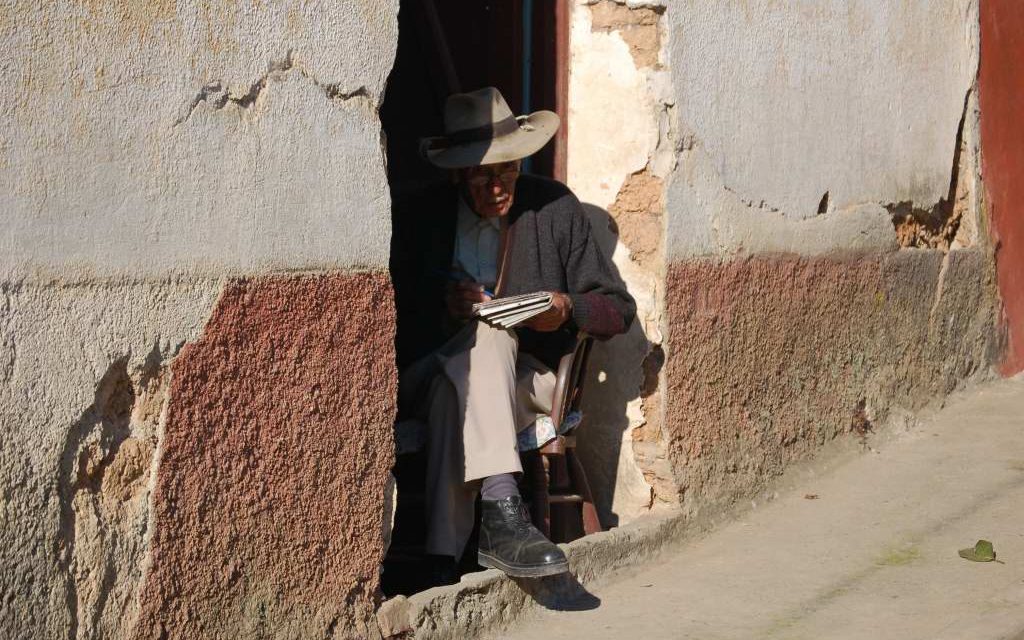

I imagine all this sounds very “political.” But it isn’t, really. It’s simply the way things are here. Pulga called the culture here a “culture of resistance,” and I don’t think he meant it in some grandiose way. It’s more like the way a spruce at timberline, dwarfed, oxygen-starved and lightning-scarred, resists by merely existing. You can see it in the faces. Since our return yesterday there has been a festival commemorating the Bolivian Revolution of 1809, and people have been celebrating on the plaza in Coroico — the most amazing variety of faces I have ever seen, from rosy Teutonic tourists to deeply blue black Afro-Bolivians, sharply-notched Inca profiles and broad mestizo noses. But what struck me most about some of the faces were the marks of resistance. Resistance to hunger, untreated disease, unhealed injury. Here no teeth. There a cheekbone smashed and an eye gone. There a burn extending under the collar like the map of a continent. A scar like a railroad across a nose. A dog with one eye. A man in a wheelchair navigating a world of steps and slopes. And on every face over forty, lines. Deep lines of laughter, worry, anger, surprise, survival.

But there is more to it than resistance. The people of Tocaña have formed a musical and dance troupe called Saya. It is a combination of African and Aymara rhythms and song, call and response, with rhymed couplets on everything from culture and tradition to current events and politics. They performed in the plaza yesterday as part of the Independence Day celebration, and the crowd loved it. It reminded me of the Micronesian stick dances that the Refalawasch perform on Saipan, and it had a similarly intense combination of joy, cultural assertion, and at moments an almost solemn seriousness.

Finally, of course, there cannot be a fiesta in Latin America without things that go BOOM. We were prepared for, and slightly underwhelmed by, the fireworks display in the Plaza on Saturday night, after having witnessed the amazing “burning castle” contraption they set off in Ecuador when we were there in 2001. But we were unprepared for the artillery and automatic weapons fire emanating from the drug police barracks this morning at 6 am. The barracks is very close by our hotel, and the explosions were incredibly loud and sounded a lot like a terrorist attack. There were three loud explosions that rattled the windows, followed each time by bursts of machine gun fire. Car alarms went off, and there was shouting. I rolled out of bed, camera in hand, wondering what I was getting up to witness and whether life in Coroico had just gotten a whole lot more dangerous. Elena said later that her roommates all got up as well, convinced that the hotel was about to be robbed. But the hotel staff, who were awake to start the day, just shrugged. “They do it every year on Independence Day,” they informed us. And sure enough, the shouting from the barracks was transforming into slurred army drinking songs. So we shrugged as well and headed back to our rooms for another hour of sleep.

There is more to tell, of course, and the story of coca and cocaine is complex in ways we have only begun to fathom, but I’ll give “la palabra” to Beret. We miss you and hope you are well. – John

*****

Living here, especially engaged in a project as we are, is a process of learning and sifting through the various, sometimes contradictory stories we are told. There are differences of perception and opinion about virtually everything. We have learned over the years that we can’t understand an issue without attempting to learn about the larger context, especially the history and cultural traditions at work here. When John wrote about “coca es vida” (coca is life), what came to my mind is that for the farmers, no viable alternative has been found. For the more urban people, there’s great hope for the future in tourism. But tourism changes local culture, as we see here in Coroico, and that’s a complex subject.

I have been reading a monograph on the Yungas, where we are, published in 1929. It was written when the old road was in the planning stage and was slated for construction. Before that, people traveled on the backs of mules. The oldest man in Tocaña, Don Manuel, lived his first thirty years as a slave and told us of the beatings he received at the hands of the “bad masters”. He also finally got to go to La Paz soon after World War II. He walked – three long days there, three days back. And now he lives on a tiny patch of a former hacienda. He’s blind and he’s waiting out his days with his ancient wife. They have no electricity, sleep on wooden pallets, and their clothing hangs from a couple of rafters. We had to take refuge in the one-room adobe-walled sleeping house during a dramatic deluge and windstorm. One part of the tin roof began to flap in the wind and it wasn’t at all clear it wouldn’t blow away. Where we lived in Micronesia, pieces of flying tin roof actually killed people during typhoons.

But back to the monograph. There’s a long, thoughtful letter in there from Dr. Ascarrunz explaining to the Secretary of the League of Nations that coca and cocaine are different things, that Bolivians produce and consume coca, which has many health benefits (which have since been studied by reputable U.S. and European scientists), coca is Bolivia’s long-standing tradition, and that even in the 1920s growing coca earned farmers more revenue than growing other crops. Lastly, and most important, Bolivians did not manufacture, consume, buy or sell cocaine. He also wrote that it is impossible to intoxicate oneself with the coca leaf, which is true. Several poisonous chemicals are required to turn the one crucial alkaloid (among dozens of innocuous fellow alkaloids) into a dangerous and addictive substance. In the late 1920s, Bolivia exported only a small amount of coca that was turned into cocaine – by pharmaceutical companies in Germany and England. As I interpret what he wrote, the plea seems to be to let Bolivia continue with its tradition, not to intervene in its domestic affairs (as the League of Nations had done, for coca and cocaine had been conflated and even labeled “narcotic,” which is an incorrect classification), and to work to manage the cocaine problem where it was created – outside Bolivia’s borders. This seems to me to be the argument still, except that there’s a great deal more abuse of cocaine and everyone knows that some of the coca grown here is diverted into illegal drug production. So coca is more morally complicated and a more ambivalent, painful topic now, nearly 80 years later. I assume that USAID’s efforts to support alternative agriculture are in good faith, but with the legacy and habit of corruption among government officials, it’s hard to imagine real success. Also, people here are not going to give up their coca. It provides nutrition in a land of fairly pervasive malnourishment and it would be somewhat analogous to our giving up coffee, tea, and Coca-cola all at once. As Paige puts it, “coca is to cocaine as grapes are to wine. I eat grapes and it’s fine. I don’t like wine.”

We had a rich experience in the small town of Tocaña. As John recounted about our time there, after having our wish to film be politely rebuffed, one thing led to another and we ended up interviewing the town leader about trust, mistrust, cultural issues and the community. Then we were allowed to film a bit – making adobe bricks, the school, the church – as long as we did not film their cocales (coca fields). We later interviewed Don Manuel, Pulga (the Quechua anthropologist who lives there), and Father Victor, an Afro-Bolivian Catholic priest who was our host at the one alojamiento (lodging place) in the village. We loved the quiet of the place, the narrow paths that link one family to another, as the houses are spread out across different faces of a gently sloping mountain. We learned a lot in our brief stay, and Elena and I drank warm beer with a number of locals, including Johnny and Pulga, at a wooden table outside a store run by an Aymara man. Half of his one-room house was his sleeping area, half was his store. When I asked where in the world they would travel if they had the opportunity, the unanimous, soulful answer was Africa. It is thought that the people of this village are descended from slaves originating in Angola, the Congo, and perhaps elsewhere, but no one is sure.

We crowded into the back of a jeep taxi the next morning for the ride back to Coroico, just in time for the Festival Agraria (Agrarian Festival) and a spirited music and dance performance by the Saya, the pride of Tocaña. It was wonderful to see Coroico full to the brim with people from the campo or countryside and to see the respect people have for one another when they gather for an occasion of civic and regional celebration.

This past weekend was also the celebration of the Grito de Libertad of 1809. Grito means shout, and in the predawn the next morning we were startled awake by what sounded like a bomb going off, followed by gunfire. We thought some terrible riot had broken out due to all-night revelry and who knows what else. As John mentioned, it turned out that the “grito” was being expressed by the local drug eradication soldiers whose barracks are very close to the hotel where we live. In the course of the daylight festivities down at the plaza, schoolchildren presented skits, poems, and music. Speeches by dignitaries preceded and dances by various fabulously dressed troupes followed. I particularly loved the ballet folklorico from La Paz, which struck me as having the elegance of tango and the lifeblood of salsa. When you think of how recently the people of this country truly won their freedom – the indigenous people, who are the vast majority – by which I think I mean feeling free to try to better their own destinies, the celebration of liberty is very powerful. The people here deeply value what they have and who they are. They are protective of threats to their sovereignty and to the prospect of a better future.

We’re at the half-way point of our trip, and the kids have done a fine job of doing their best to adapt to life here. Tomorrow Paige begins volunteering in an English class at a local secondary school. Yesterday Marcus had his first secret admirer, who turns out to be not so secret after all – a little girl who made him an “I love you” valentine accompanied by a bouquet of red hibiscus and a pack of Skittles. We found these on our doorstep. He was pleased to be the object of such attention, which came in the aftermath of his playing pool with a gaggle of very young local girls, none of whom speak English. They spelled his name “Make”, which would be pronounced mah – kay. Cute, no?

I go to La Paz tomorrow, camera in hand, to document a bus driver’s story about driving passengers for ten years over the old road. John follows on a different bus. We will come back with a bunch of mountain bikers, John on a bike (he couldn’t resist) and I in a jeep trying to get some good images of this mountain biking phenomenon. We will be interviewing the head of the most highly reputed mountain biking company in La Paz. We realize that if we focused on a single character and a more easily defined and containable story, it would be easier to shoot and make our film. But that is not what our curiosity leads us to do, nor what we want the film to be about. In the end, we will probably have a longer, more involved story to tell than we imagined, and that will mean harder work in the editing room. We have a history of taking the hard road, like the people of Coroico, so that seems entirely fitting.

Be well, everyone!

Beret

We had over 500 people for the premiere of “Penny & Red” at the Boulder Film Festival yesterday. Penny was in good form for the Q&A, and the film got lots of laughs — even in places where you’d think, hmm, was that moment actually funny or do they not know quite how to re…act to that information. . . . I feel deeply grateful to have Mom still here, still participating, still casting Secretariat fairy dust out to her fans after 40 years.

We had over 500 people for the premiere of “Penny & Red” at the Boulder Film Festival yesterday. Penny was in good form for the Q&A, and the film got lots of laughs — even in places where you’d think, hmm, was that moment actually funny or do they not know quite how to re…act to that information. . . . I feel deeply grateful to have Mom still here, still participating, still casting Secretariat fairy dust out to her fans after 40 years.