I take this blog category from an article I wrote for my high school’s alumni magazine . . .

Confessions of Secretariat’s Slower Brother

By John Tweedy ’78

St Paul’s Alumni Horae, Spring 2015

“My mother owned Secretariat.”

Ever since the summer before my Third Form year at St. Paul’s, my life story has featured that sentence, a flashing non-sequitur in an otherwise pedestrian paragraph. As a racehorse, an athlete – a sheer force of nature – Secretariat would have upended the lives of any humans who might claim to “own” him. He certainly upended ours.

His 1973 Triple Crown sweep, setting records that still stand today and winning the Belmont Stakes by 31 lengths, shocked the country out of its Watergate torpor. He graced the covers of Time, Newsweek, and Sports Illustrated all in the same week. A postman delivered 250 pieces of fan mail to our home. Every day.

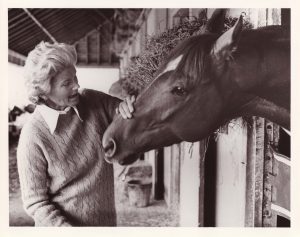

But my mother, Penny Tweedy (now Chenery), also played a key role in Secretariat’s story – a role for which she had, by twists of fortune, been well prepared. She bred him into an intact racing stable that, two years earlier, she’d had to cajole her siblings not to sell. She had in place a brilliant trainer, jockey, and backstretch team. She had even been through a dress rehearsal the previous year, winning the 1972 Kentucky Derby with Riva Ridge. And then, once Secretariat’s championship season evolved beyond any expectation, she did her best to do him public justice. Penny adopted a democratic persona for the TV audience, broadening the appeal of a sport previously dominated by aristocratic snobs. She was more parental than possessive, reflecting her enthusiasm for the horse’s achievements to fans of any class. And yet she maintained the social graces of her boarding-school upbringing, sending a personally-signed response to every one of those pieces of fan mail. She was somehow both a ham and a lady. Forty years later, the racing world still loves her.

The 2009 film Secretariat, starring Diane Lane, vividly captured this partnership between horse and owner in the mythic Disney tradition. The movie even features a ball scene, with my mother dressed in a gown and elbow-length gloves. Thus elevated to the status of Disney princess fable, Penny’s story has delighted a new generation of girls who dream of powerful horses. Mom still gets fan mail, now often gushing, “You are such a great lady! I’ve watched your movie at least 20 times!”

Thus Hollywood becomes our historian. But as my mother puts it, “In some ways, that’s a lot of BS.”

In real life, my mother belongs to the World War II generation, with the salty vocabulary to prove it. She’s like many of the mothers of my formmates at St. Paul’s – smart, ambitious women who went to good schools, served capably during the war, and were forced back into the kitchen in the late 40s, where they sweated, and fumed, for the next quarter-century. Mom worked in a naval architecture firm until D-Day, went to France with the Red Cross in 1945, and came within a month of finishing her Columbia MBA — until her father insisted she quit, so she could plan her wedding.

Giving up hope for a career lit a slow fuse. By the time of my 1960s childhood, our household was a tense place, a genteel clapboard front in the wars of gender and generation that marked the era. The battle lines were sharper, the injuries deeper, and the losses more permanent than today’s “family-friendly” films convey. When Mom had the opportunity to escape and achieve, she grabbed it with both hands.

The youngest of her children, a skinny eighth-grader recently transplanted from Colorado, I felt dazzled by her brilliance and lost in her dust. Secretariat’s grandeur thrilled me utterly. And to celebrate his victories in the elite recesses of famous racetracks — where waiters impassively served champagne to a twelve-year-old boy – felt giddily surreal. But these experiences left a hangover too. My adolescent ego grew increasingly frustrated at being famous for the achievements of someone else. And I resented my parents’ public efforts to portray their marriage and family as intact and happy, when privately we had fallen apart.

By 1974, when I arrived at St. Paul’s — where both my father Jack and my brother Chris were alums — the last thing I wanted to talk about was Secretariat. Thankfully, the school largely obliged. I’m sure my peers knew I was a kid from a famous family – like the Senator’s son, or the girl who came from European royalty — but none were gauche enough to mention it. This pattern continued into college, where I became so silent on the topic that friends would know me for a year before it arose. When disclosure became unavoidable, I would casually mention that my mother owned “a horse called Secretariat.”

“Dude,” one classmate laughed. “That’s like saying your dad is a guy named Richard Nixon.”

And so the non-sequitur took form, a brilliant fragment casting an ill-fitting shadow, persisting for decades. When the Disney movie came out, my brother Chris joked, “I’m glad they made up the family part. In real life we were neither functional enough, nor dysfunctional enough, to make a good movie.”

It struck me that Chris’s remark stated the problem dead on. As a culture, we require our public figures to be either paragons or fallen, either accepting the Oscar or checking into rehab. In truth, celebrity often combines elements of both. What Mom and I both needed, for our separate reasons, was to weave the public and personal narratives of her life into a single braid.

My wife, Beret Strong, and I have made documentaries since the 1990s, and I had long thought of Mom’s pristine film prints of Secretariat’s races and other family archives as rich sources for a film. Plus, from the fearlessness of a 90-year-old perspective, Mom now wanted to talk – about how her own childhood was marked by conflict and abuse; how her father encouraged excellence but insisted on submission; how her ambitions chafed under the housewife role; how her anger grew; how it felt to take over her father’s stable, to find victory with Riva Ridge but to receive a kind of grace in Secretariat’s transcendence. How, at the same time, she lost her father and her marriage. How she found a new path in the loneliness and liberation of fame.

The resulting film is Penny and Red: The Life of Secretariat’s Owner. A documentary should offer a fact-based perspective but not make a pretense of truth. In my personal interviews with her, Mom and I aimed for catharsis, and we found it. But as director and editor, I tried to steer between the opposing shoals of hagiography and exposé. And a documentary still needs a story, with a plot that obeys the laws of ancient drama.

Among those narrative archetypes is the “hero’s journey.” One of my grandfather’s father’s rules of thoroughbred etiquette was, “Don’t embarrass the horse.” If Penny’s life has elements of heroism, it is partly because she has worked for four decades to live up to an animal that many still think of as the paragon of his sport.

But Penny’s journey is also simply that of many women of her era. I think the women of the “Greatest Generation” were heroes – along with the men who fought and died — whether they became famous or not. And in exploring Penny’s private struggles and triumphs, as well as her public glories, Penny and Red aims to suggest that, from the perspective of those who live it, a heroic life is no fairy tale.