Queridos amigos y familiares, Bolivia — June 25-July 7, 2011

John here. Today I have dined on tubers shaped like giant grubs, been savaged by sand-flies, and been kissed — and then slapped — by a very saucy squirrel monkey. We are back in Bolivia’s Yungas Valley, where we spent two months in 2006. During one of our letters home that summer, Beret said she would love to come back in five years to see how the valley had changed, how the place and the people weathered the moments of transition they were going through back in those days. Well, as she does with many things to which Beret puts her mind, she has made it happen. We are back to finish the documentary video projects we began back then, telling the story of the “world’s most dangerous road” and the people who earn their living from it, the tourists who flock from countries so safe that they must travel abroad to buy risk, mountain-biking down the road, while locals send their kids up the same road on rickety pickups to study their way to a better life. And as we did five years ago, we are having a blast.

In 2006 we shot over 40 hours of video, and we came home with a sprawling sense of landscape, issues, and people. But somehow, the story kept eluding us. The raw footage split into two documentary film projects: the first, a simple portrait of dance and cultural resistance in the Afro-Bolivian village of Tocaña; the second, an unwieldy, double-plotted hodgepodge about adventure tourism, coca politics, and economic hardship on the “Road of Death.” Since then, successive rough-cuts of these films have sat on the hard disks of our editing computer like overgrown adolescents in the basement, refusing to grow up, but too old to be still living at home. Friends and colleagues would ask, “What are you working on these days? How is that Bolivia thing going?” And we would respond with embarrassment and later resignation about the fact that we were just plain stuck.

Then this year, Paige graduated from high school and went off on her first adventures of adulthood, and Marcus gathered his moxie to attend a month-long sleep-away camp. So Beret and I decided to celebrate this taste of empty-nesting with a trip that would reconnect us to the days of travel before kids, when we blew with the winds of our own desires through Latin America, Africa, and Europe. I’d only dimly remembered that sense of freedom, one of my chief pleasures in travel. And coming back to Bolivia did not immediately present itself as the best way to regrow those wings of youth. In fact, Bolivia felt a bit like the wall I had been banging my head against for the last five years, and part of me was at times ready to let go of the project, as a failed attempt to tell a story that just wouldn’t seem to fit together, a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle with only 389 pieces in the box. But the one time I gave voice to that feeling, Beret looked at me in shock and said firmly: “We are NOT giving up. We need to go back.”

I knew this was right, but I didn’t know why it was right. Because I didn’t really know how we were going to get unstuck. When we visited in 2006, the old “Road of Death” was about to be replaced by a new, modern highway passing over a different route, which meant that the mountain-biking groups would no longer have to share the road with the buses and logging trucks that gave the experience its main ingredient of actual risk. I mean, the road is still a steep, one-lane, dirt shelf with 200-meter cliffsides and frequent landslides. But if you’re not at risk of being run off it by a gigantic bus on a blind corner, the challenge of staying on the road becomes much more manageable, and the “danger” recedes to a level not much greater than that presented by a jeep trail back home. On the locals’ side of the equation, once the road was relocated, the town of Yolosa, where we had done most of our shooting, would suffer the loss of its principal means of livelihood. We had later heard that, after the new highway opened in late 2006, Yolosa indeed seemed abandoned, and that the mountain biking companies had largely taken over the old route as their own theme park of perceived risk, an “authentic” travel experience with most of the authenticity now drained out of it. If we went back to do more shooting, would these realities simply be confirmed, making our story less coherent, or perhaps more depressing, than ever?

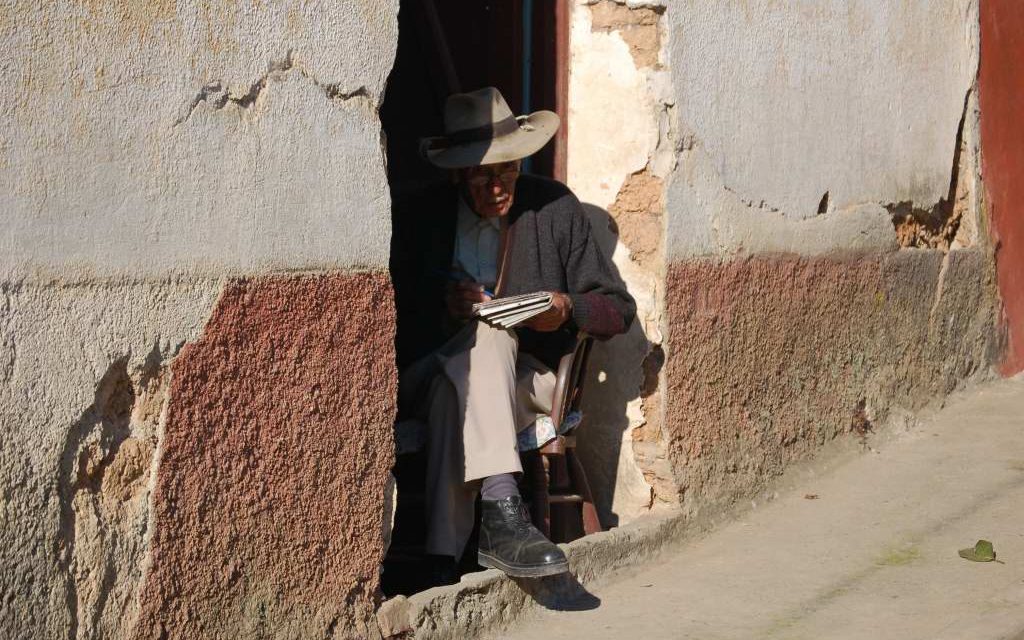

Still, our curiosity, our resolve to finish, and our memories of love for this corner of the world brought us back. Last Friday we flew through the fleshpots of Dallas and Miami, landing without a hitch in the wee hours in the thin, frigid air of La Paz. Beret had dreaded this leg of the journey because of its extreme altitude (nearly 13,000 feet in La Paz and over 15,000 at the high pass leading to the Yungas), and her fears were not misplaced, as she developed a fierce headache during the first twenty-four hours. With Beret abed, I had the first day to wander the city by myself, navigating the steep streets and profuse sidewalk commerce by memory from five years ago. I needed a cheap wristwatch (one of my thief-deterrent strategies when traveling) and so I started hunting. Shopping in La Paz is a completely asynchronous experience, in which past, present, and future coexist simultaneously. On every sidewalk is a row of women, dressed in traditional pollera skirts and bowler hats, selling mostly fruit, root crops, and fried breads, as they have done for centuries. Right behind them are businesses selling computers, cell phones, stove parts, treadle-powered sewing machines, ribbons and lace, huge bags of confetti for special occasions, raw fish, soccer jerseys, refrigerators, dynamite, dried llama fetuses, and pirated Lady Gaga CDs. All of this commerce takes up any available pedestrian sidewalk space, so to navigate on foot you have to walk out in the street, next to the line of cars and buses easing their way past with polite taps on the horn and just inches to spare. For relief from the congestion you can enter old stone buildings into labyrinths of kiosks selling bolts of bright fabric or auto parts, with high ceilings and staircases leading God knows where. And each business, each half-block, sells almost exclusively one type of item, so if you want a cell phone you go to one stretch of stores, and if you want an MP3 player you go up a half-block farther. I thought a cheap digital watch would be among the electronics vendors, but they kept telling me “Más arriba” (go higher), so I kept climbing the steep grades, stepping over sidewalk displays of bubble-gum and fried pigs’ trotters, alternately delighted and nauseated by the succession of smells, mystified at how so many vendors could keep afloat, and amazed at how tightly-organized it all seemed to be. Finally, just after passing a kiosk that sold literally nothing but VHS video cables (hundreds of them, twisting like black snakes with white, red and yellow heads) I came upon a man sitting on the sidewalk behind a large glass case full of wristwatches, pocketwatches, analog, digital, cheap, fancy, every kind of watch I could desire. Five minutes and $3 later, I was on my way back down, navigating in reverse order the succession of vendors (let’s see, did I turn left here at the toilet seats?) in order to find my way back to the hotel.

The next day, we hired a very calm, thoughtful driver to take us up over the pass and down to Yolosa. We opted for the new road, which we had only seen part of in 2006, on a clandestine shoot before it opened. It really is an engineering marvel, full of cantilevered bridges and switchbacks. But it is no scarier than Loveland or Berthoud Pass in Colorado. In order to round out our footage (and I confess, for the sheer I’m in Bolivia now and I get to do whatever the **** I want joy of it), we shot standing up through the sunroof as the high Andes rolled by, not quite managing to climb back inside before the drug checkpoints came into view. But the narco police didn’t care.

We arrived at the Senda Verde Wildlife Refuge and Eco-Lodge, one of the new developments since we were last here, in a state of elation to be back. I’ll let Beret tell the rest, except to say that it is challenging to maintain your composure while conducting a video interview with a monkey sitting on your head and sticking its surprisingly human little fingers into your ear. But now I know it can be done, and I’m a better person for it.

****************************************

My turn! Beret here and, having just read what John wrote, gratified that I got credit for our return to Bolivia. We had a brief chat about going to Italy instead, but that felt pretty expensive and touristic, if that’s a word, and I like to go where life is a little more raw. That’s one of the exciting things about the jungle – you realize that it could pick your bones clean. But since we’re taking the path of greater creature comforts, we haven’t had such close encounters, though I did manage to get my thumb bitten by a pick-pocket of a Capuchin monkey this morning and our first night here John found the tiniest, most darling little baby of a scorpion lost in the oceanic dimensions of our bedcovers.

It’s very beautiful here, with a river that can sweep away whole towns during its flood stage of December through February. I saw some men with shovels and wide, shallow wooden bowls and I thought… hmm, they look like gold miners (only the pan was the wrong material). And that’s what they were. We’re at a refuge for Amazonian animals rescued from various bad fates, and there’s a cacophany of irridescent, large wild birds and various species of monkeys. Something here, I haven’t figured out what, has a cry that sounds almost human. The monkeys are my favorite, especially the spider monkeys, which are remarkably elegant whether walking, climbing, or flying from tree to tree. They climbed in our laps yesterday morning because it was cold, proceeded to wrap themselves into balls, and close their eyes in bliss as having a warm lap and chest to lean into plus a little bit of grooming to boot. (Not being a genius with monkeys, I just treated them like cats.) The smaller monkeys will leap from anything to anything, and one decided, while we were filming an interview with the reserve’s co-founder, that the top of John’s head was desperately in need of some nit-picking. He (or she) ate peanuts all the while, so pretty soon there was quite an ecosystem on John’s head. Our interviewee was saying serious and eloquent things, John was trying not to laugh, and I was trying to keep the monkey from mauling the camera, as it very much wanted to climb all over it.

I will be very sad to leave here tomorrow, but we are off to Coroico, our old home, which is up the mountain about a thousand vertical feet and where we hope to cross paths with our niece, Elena, who helped us film here five years ago. Back to the birds for a moment (I can’t bear to stop talking about this wonderful place), they are so formidable that the one domestic cat I’ve seen must know it would be in shreds if it so much as cast an eye in their direction. The birds groom each other, eat, and squabble. There’s a baby alligator with a pool of its own and a large Andean bear that looks a lot like an adult Colorado black bear (with an extra lustrous coat – he gets fed raw eggs, papaya, and coconut, among other things) except for the distinctive yellowish mask on his face and his long, narrow nose. We watched him being fed this morning. It took a while for him to get interested in his food, but he came downhill, knocked his massive papaya off its perch, took one large chunk of husk off of his coconut, and stood up on his hind legs on his side of the fence to inspect us. We were all of three feet away, but there was an electric fence that was reputedly in a good state of repair. There are a dozen volunteers here, plus local staff, and the volunteers are young travelers from Europe and other places who heard about this place, or came to it after biking the World’s Most Dangerous Road, were as enchanted as we are, and asked to stay on. I would too if I were 22.

Speaking of our age, the other evening John said to me, “You know what we are?’ This was after we’d shot a badly played game of pool (where we bent various rules) and the volunteers had come in to occupy the movie-watching and pool-table space for their evening’s leisure. We could feel that it was their space, at least in a certain way, so after our game we went back to our large cabana. That’s where John posed the question. Somehow I could tell this question carried a bit of freight. I waited, and then he said, “We’re their parents.” Oh! Indeed! Yes, he was definitely right. No way can we pass for young, hip people. And John lathered it on some more: “No one wants their parents around when they’re doing their own thing.” (He probably said something more elegant than “doing their own thing,” but I can’t remember now.) And suddenly I saw myself through their eyes. Thanks to John, I can’t go back to my ambiguous, free-floating traveler’s identity that didn’t have a lot of ideas attached to it. THANKS, JOHN.

But, you know, we are finding ourselves to be the ones in the zoo, and that is wonderful. This place is animal habitat, and we are just interlopers. The dining room has a sort of tin roof and chicken wire for walls. The spider monkeys go “thwack!” loudly onto that roof at any moment. Various dogs, monkeys, birds and other animals are on the outside looking in at us, very much like we were aquarium animals and they had paid admission to be entertained.

We miss Paige and Marcus, but Paige feels not so far away (we’ll be even closer when we get to Isla del Sol on Lake Titicaca), though she’s currently a few thousand feet higher. Marcus feels farther away, but we know where he is and so I can bring him almost close in imagination. It’s really a shock to be reduced to just the two of us – with almost acres of time to talk, so much time in fact that we run out of things to say. If we weren’t so focused on our filmmaking during these days, it would be stranger still because we’d be reading and writing and walking and gazing into the middle distance, maybe as we did 20 years ago, when we were finally finishing our schooling. I remember long, slow mornings of coffee, the Sunday New York Times, and my favorite cat on my lap. Into the middle of that came a fierce want: baby! And holding the spider monkey in my arms yesterday reminded me how fine it is to hold a baby (though I confess this one was all hairy black arms and twining tail).

Lest you think I don’t care a whit about the film (and John does), here’s the deal: I am now very glad we didn’t finish the “road film” (as we call it) because it’s going to turn out better and truer to its subject than it would have had we called it done before now. John gets the credit for this. I was never going to give up and say “no film, it all goes in the trash” (are you kidding??), but I was at one point ready to say, “It’s good enough,” which it wasn’t. I have long admired filmmakers who take years to make their films – because the story takes years or building the relationships necessary to document the story takes years – and felt that they were our betters. After all, look at that staying power. But now we can say, well, we did that once – we had the patience to wait until the story told us it was sufficiently complete.

When we got here, we reread the six ‘travel letters’ we wrote about and during our summer (well, the Andean winter) in Bolivia five years ago. It’s a portrait of dawning awareness. We kept wondering about this and that, and sometimes finding answers. Now we’re again feeling the pleasure of revelations. Talking again with the characters in our film after five years has been really interesting, and I keep learning things, such as that the former truck stop village of Yolosa actually has a municipal water supply. I thought they piped their water out of the river (and who knows what goes on upstream), but in fact they have cleaner mountains water and use the river for washing clothes and bathing. I almost wrote “and for runoff from their sinks, drains, and toilets,” few in number as they are, but that would be an assumption. And my assumptions of the past have clearly led me astray.

La Paz is fascinating in the way John expressed. It’s also amazing to see such a vertical city, houses clinging to steep mountainsides with a narrow valley in between. I love the old colonial buildings best, but the day we were there and I got progressively sicker, I was thinking that if someone wanted to put me out of my misery (a nail through the skull was what came to mind), that would be okay. It was magical thinking, the kind that strikes one at high elevation, and my goal wasn’t to die, but to be utterly without suffering. We are headed back to quite high elevation for the last week of our trip and I think I am doing that based on hope (which feels like faith and almost like prayer) that I can get through to the other side, where my body comes right with the environment and I can enjoy the bliss of Lake Titicaca’s brilliant blue water and the sere, barren, and beautiful landscape of the altiplano.

************************************

Greetings from a fabulous balcony at the Hotel Esmeralda in Coroico. It’s still Beret at the helm. This is our old haunt, the hotel where we lived (and lived through the glories and low moments of the eternal buffet) for two months in 2006. We had a double-decker room two doors down from our current room. The kids’ beds were hobbit-sized, meaning too short for Paige, and there wasn’t even a door between the upstairs and downstairs of our room. (Parents, time to pause: can you imagine that for two months?) It’s as beautiful here as ever, and we’ve got our fingers crossed that our niece Elena will somehow roll in before night. The chaqueo, meaning the burning of fields (as a way to get them ready for new planting), is starting up again, and it drives John crazy. Over time, it fills the valley with smoke and bothers every living thing. It’s technically “prohibited”, but that doesn’t mean much around here. An out of control chaqueo burned for days over Yolosa a couple of years ago, killed the trees that were holding up the mountain, and when the rainy season came, down came the mountain, covering the road and bursting into the house of our film character, Don Timoteo, who is famous for being the first “human stoplight” on the road of death. He is now out of work, aging, and eating a whole lot of oranges, which are cheap and abundant here.

This morning we bade farewell to the Senda Verde, but not before a baby howler monkey had snuggled in my lap and a traumatized spider monkey had been caressed and stroked in John’s lap. One of the owners of the reserve is basically the alpha of alpha monkeys, but he was gone somewhere today, and two of the spider monkeys began to fight each other for the alpha position. Such fights are usually brought to a stop when the staff douse the monkeys with buckets of water, but these two wouldn’t stop and … guess what happened to them? They literally rolled off the proverbial cliffside. Even down here, there are cliffs, and below them are rocks and rivers. The monkey John held had been found shivering on the rocks below, but mainly unhurt, and he needed comfort.

Did you know that guinea hens travel in packs or pods – well, always together – and that their heads (I mean brains) are about a hundred times smaller than their big speckle-feathered bodies? Well, now you do. The coatis don’t pay an attention to humans (insects are much more interesting) and the strange ferret-looking creature that evidently has a mean bite is as curious as a smart kindergartner. As for Coroico, it’s luxuryville, as we were able to go to the bounteous downtown and buy a slice of linzer torte (from Hans the baker, someone we know from years ago) and buy a big box of coca tea so we don’t have to live without it for another minute. The Senda Verde had none and that was steep deprivation. It also didn’t serve enough food for some reason (we have theories on that), and so John had three pieces of fried chicken for lunch and was a happy man.

One thing I love about Boulder is that it sometimes feels like a small town. You run into people you know. Miraculously, that’s happening here, too, even when we don’t expect it. We were walking around downtown and I heard the voice of a woman talking on her cell phone. Dios mio if she wasn’t the very same woman we interviewed in the Yungas Room of the coca market in the capital city of La Paz five years ago, the one who complained about the U.S. government’s desire to eradicate coca. On what are we going to live? she said then and again now when I stopped to talk to her and told her that we’d interviewed her five years ago. She was just as forthcoming as before, and looked not a day older. We had also been trying to mail a letter to Paige in Peru, but the gate of the postal woman’s house was up, which means “I’m not in.” We had dropped by and then circled back again an hour later, only to be disappointed. I randomly asked the first woman I saw walking by when she thought the post office might be open and she was the post office! The post office was her front room, fancied up with doilies on chairs and family portraits on the wall. I feel like we’re in the land of small miracles.

Ten years ago, I thought it would be fun to write a book about how to take small children into the outback (ours happened to be rural, gold mining Ecuador) and entertain them with virtually nothing but … trash. (I am not joking. You can make a lot of cool things out of trash – whole cities, in fact.) Now I am thinking about my current plan, which is to do this entire trip without washing ANY clothes. Ladies, I have some tips for you on how to make your supply of underwear last three times as long as it should. But I fear that if I went into details, it might be slightly disturbing. So just imagine…. On the pants front, though, I can say that a pair of semi-dark (gray is good) hiking pants can last forever. Mine have had orange juice and beer spilled on them, I’ve knelt in the dirt a bunch of times, been monkey-slimed, and they look really good. This is day 7 and I’m wondering if I’ll even need to break out my backup pair. (-:

**************************

John here again. We’re still at the Esmeralda, and now it’s my turn to sit on the balcony and gaze over the endlessly-shifting configuration of clouds and fog in the valley across and below. The weather over the last day has turned positively wet, with rain and fog blowing through all evening and most of today. My niece Elena joined us yesterday (she was with us in 2006 as well) and we have been catching up on old times, talking about graduate school (she’s studying for a PhD in Latin American history), and taking a hike in the nearby mountains. The hike normally boasts panoramic views, but with the fog we contented ourselves with closer pleasures, such as ferns, butterflies, and — suddenly — a very large rattlesnake curled on the side of the path. Fortunately we saw him from about five feet away and stopped short before we got in striking distance. He sat there lazily, sluggish from the cold, eyeing us, deciding whether we were really going to be stupid enough to make him bestir himself. The answer, of course, was no, he could have his mountainside trail, and we would happily head back the way we came, grateful for the walk and the visitation from the ancient snake-god-from-the-mountain, or so in all his scaly glory he seemed.

Yesterday we had another memorable walk, to the Afro-Bolivian village of Tocaña, where the other of our two films is set. We walked to the colonial main square of Coroico, found a not-too-aged taxi with a sufficiently-aged driver (there’s a sweet spot in there), and set off down the vertiginous cobblestone road to the valley floor, expecting to climb up an equally steep dirt road on the other side to get to Tocaña, perched on the side of the adjacent hillside. But when we got to the riverbottom and turned towards the bridge, we hit an unexpected traffic jam. It turns out the locals in the vicinity of the bridge were having a meeting with some government officials about repairs, and the meeting was expected to last for the next four hours. I looked across the bridge and saw a cluster of perhaps 50 people standing in the middle of the roadway. At a certain moment a forest of hands shot up, apparently voting on some matter. After some consultation with our driver and some people on the fringe, we decided we could cross on foot, carrying our camera gear and daypack, and the taxista would wait for us to return. As we nudged our way through the crowd (their looks were not terrible friendly toward us trespassers, as you might expect) I was struck again by how, in this world, the road through town is the meeting-hall, the market, and sometimes even the church. And when the local people need the road for this purpose, traffic on either side patiently waits, as it would for a landslide to be cleared away.

After we humped up four km. of steep switchbacks on the far side, past coca fields and shrines to dead drivers, Tocaña itself came into view above us. Upon sweaty arrival we learned that the new health center locals had been hoping for had been built in 2007, that the Bolivian constitution had been changed to account for Afro-Bolivians as a distinct ethnic group, and that not much else had changed. We were happy to discover that the people had received an earlier cut of our film that we had sent to them some time ago, and that they were very pleased with how they were portrayed. I sat in a small house with a grandmother whose daughter was one of the characters – and who had not yet seen the film — and watched it on a small TV. Her dark face bloomed at seeing her daughter on screen. Once townspeople realized we were the people who made the film, their faces radiated friendliness. I had been nervous about going back, worried that we had created a portrait of the town that would not feel true to the people who were its subject. But apparently we did OK, and we’re arranging to ship a bunch of copies of a bilingual DVD that they can sell to tourists.

But most moving was the former truckstop town of Yolosa itself. We had also brought a cut of the “road film” to show people, a half-hour version that I had recently shown to a Rotary group in Boulder. The film ends on a funereal note, with the town’s young people performing a traditional dance in costume in front of a shrine during their annual saint’s-day festival. As we predicted back then, 2006 was the last time they danced that dance. Once the new road opened in early 2007, Yolosa died back to a remnant of its former self. Out of 80 original families, only 14 are still there. Adding to the woes, a landslide hit the north side of the town last year and destroyed the shrine they had so beautifully decorated in our 2006 footage. So when we showed the cut to a small group under the awning of an abandoned kiosk, people’s reactions were mixed — they laughed and smiled to see themselves on screen, but by the end they seemed subdued and sad to see the portrait of what they were, compared to what they are now.

And yet, there are signs of renewal. The valley environment has recovered so wonderfully with the lack of smoke, dust, noise, and trash — now that the old road no longer carries the heavy truck and bus traffic — that Yolosa is now a beautiful, tranquil place. The river flows picturesquely through the center of town. Native birds and animals have returned. The international agency that financed the new road’s construction is FINALLY about to release the funds for building a new tourist infrastructure, complete with a hotel, new, shops for receiving the mountain-bikers, houses, soccer-fields, and a wider channel for the river so that these new improvements might actually survive the rainy season for a year or two. Along with these changes, there is a new awareness among the people about their environment that was almost completely absent when we were here before. Now that they have re-oriented their efforts to earning money from tourists, they have begun to market their town as “eco-friendly,” complete with recycling bins and freshly-painted slogans. Greenwashing? Sure, to some extent. But it’s partly genuine as well. Perhaps the biggest change has to do with the landslide that hit the north side of town. It was caused by the fact that the townspeople had set a fire to a nearby hillside the year before to prepare it for planting, and the fire had gotten out of control and burned the trees on the steep slope right above town. The lack of trees made the slope susceptible to erosion, so the next year, it all came crashing down on their heads. Thankfully, no one was killed. But a lot of townspeople are now opposed to the traditional burning practice, which, by the way, the national government has now made illegal. In 2006, when I would complain about the smoke and destruction, locals would just shrug. Now they are actively trying to find new ways to prepare their fields.

The Senda Verde animal refuge is part of the change too. The owners are Bolivians from La Paz, so they might as well be foreigners as far as the locals are concerned, but they employ local people to staff the place, and the animals’ effect on them is as profound as it is on the foreigners. They also invite local school groups in to tour the grounds, teaching the kids a new way of thinking about the planet and their place on it. Yolosans are a little nervous about having so many “wild animals” so close by, but they are realizing that this is their future, and the initial distrust they felt for the project appears to be waning.

The tourist trade is ramping up in other ways as well. The leading bike company has installed a three-legged zipline over the town, employing more local youths in a job that requires them to learn English and maintain the safety equipment. The high-pitched whine of the thing probably drives them bats as tourists whizz over the town, but it gives the locals another way to keep the gringo dollars in town for a few brief moments before they head off to test their bravery on another “dangerous adventure.”

Our two main characters from Yolosa, Mary and Julia, are both women in their fifties. Mary is outspoken and judgmental, with short red hair and a businesswoman’s directness, whereas Julia is quiet and traditional in her long black braids. But they are both survivors. As Mary showed me the architectural drawings for the new Yolosa, I asked her what her own new place is going to look like. “This isn’t for me,” she said. “This is for the kids. I’ll be dead in five years. I’m old already.” When we protested that this couldn’t be true, she told us of her diabetes, of her hope that she would live to sixty but her expectation that she wouldn’t get much father than that. Julia, on the other hand, has living parents in her eighties and appears ready to live at least that long. Other than the fancy gold dental work she had done, she hasn’t aged at all. Probably all that coca-chewing keeps her young. Anyway, we promised them both we would be back before another five years pass. And when I return, I fully expect to see them both thriving.

Well, I’ll give this back to Beret. If you’re still reading this tome, you have as much stamina and patience as the Yolosans! Thanks for listening.

********************************

Beret here. Yes, we’ve been ruminating for days on the fact that most people will not want to read anything this long. Maybe a good machete job is the ticket. Speaking of machetes, young boys carry them, working alongside their fathers. We miss our monkeys, and have had to make due with less glamorous fauna – wolf spiders, a rat on our balcony, birds shrieking in packs or circling silently, a cat in an overly small sweater, and some sweet old dogs. As for Mary, our Yolosa shopkeeper interviewee and friend, I found it very poignant that at 52, she’s thinking of her death. We are her age-mates and we figure on 30 more years at least. Life is hard on Bolivians and their lifespans are significantly shorter than ours although I could get monkey bite fever any minute and John learned from our Lonely Planet Guidebook, which we have had for years but clearly didn’t read, that the chuspis (sand-flies) that plague everyone here can carry leishmaniasis, which can infect internal organs and kill you. Wahoo! If the locals are worried, then I cock an ear. Otherwise, why worry, eh?

I see that John didn’t mention that he just HAD to do the zip line. And he just HAD to do it with our best video camera in his flying hand. It was all fine, but only because the zipline staff sent a handler with him on the wire who could do the braking so John didn’t drop the camera or smash into the bumper for runaway tourists at the end of each leg.

It is COLD here. There being no such thing as heat in Bolivia unless you live in La Paz and are upper class enough to have a space heater, alpaca comes in handy. I’ve been sleeping in pajamas and socks and wool sweaters and my favorite alpaca hat, all this in addition to blankets. I also, as Marcus will tell you, have a reputation for being a wimp.

Tomorrow we go back to La Paz, and the next day on to Isla del Sol. We’ve had a great time listening to Elena share her knowledge about Latin American history. I’m reminded of our student days, when our heads were full of what we were learning. Now my thinking is more … dispersed. Here, I grow prone to a certain empty-headed meditative state. I would hazard a guess that Bolivians live much more in the present than Americans. That suits me right now. Here’s what I like so much about Bolivians: they’re hard workers, honest, and (most of all) have a very solid sense of pride and identity. They believe their country is full of wealth – mineral wealth and fertility and beautiful ecosystems – and so they don’t say they are poor. They will say that their governments (and the Spanish before them) have robbed the people.

As for small dishonesties, our taxista of yesterday was hoping to be hired to take us back to La Paz tomorrow, but his Toyota is too old and rickety for that. John asked how old it was, and after a slight pause for cogitation, Marcelo answered, “Five years.” John’s estimate was 15, given the car’s state of technology. Can you blame Marcelo? And his price to La Paz was less than half of what we paid to get here, so….

It’s time for bed, so I’ll sign off for now. All of you in warm places, please radiate a little in our direction. Even my feet are cold within my thermal socks.

********************************

Beret again. Greetings from gorgeous Isla del Sol on Lake Titicaca. To set the scene, it’s now nighttime, there’s no place to plug in any electrical object in our hostel, and what light there is is golden, from a single bulb overhead that dims at random. This island is very beautiful and unpopulated. It juts straight up from the very blue lake and across the water we can see the magnificent 20,000 ft. peaks of the Cordillera Real. We are in a village called Yumani, populated by happy kids, hardworking adults, burros, amorous dogs, llamas, a few pigs, and a lot of sheep and lambs. The burros do their loud burro call every so often and it seems to be their way of talking across distances or calling out their hunger. Sound carries far because there’s so little vegetation, though there are eucalyptus trees and beautiful flowers. We’re in the tropics, after all! The steep hills are terraced, so people can grow potatoes and a plant I don’t know to feed the sheep. The rooftops are tin (which glints in the sun), thatch and reed, and tile. The buildings seem to be adobe. The days are somewhat warm, but the nights are around freezing, and I have been sleeping for days in alpaca socks, pajamas, a wool sweater and an alpaca hat. My biggest packing regret is not having brought long underwear on this trip. So, here I am in bed, John dozing off beside me (he’s sick but starting to recover), in a shirt, two sweaters, and a Gore-Tex shell, with blankets atop. And Bolivians are very good at blankets because they have to be. Isla del Sol (Island of the Sun) is one of the most beautiful and peaceful places I have ever been. We took a walk (which felt like a hike, since every step up at 13,000 ft. is a big deal) up a hill and then sat outdoors and watched the day slowly wane. We ordered a pizza, having skipped lunch and been given a skimpy breakfast at our cheapest hotel yet (under $12), and waited for the dough to rise and the pizza to be made. Long years ago, we’d make jokes in Mexico while waiting for food. They went like this: now they’re catching the chicken, now they’re plucking the chicken, and so on. In those days (and maybe still?) a bowl of chicken soup might easily have a pair of chicken feet (I’m talking yellow talons) sticking out of it.

Last night we were in Copacabana, the embarkation point for boats to this island. We got on a boat with a bunch of young travelers (mainly Latin American, with some European thrown in), but the lake was rough and the boat was overcrowded, so they said they’d take just the ones who were going “one-way”, meaning staying on the island. They got a new, smaller, nicer boat, but communication was so poor that everybody mobbed onto the boat. I got on after the seats were all taken, and John was stuck on the dock. That wouldn’t do, so I got off and we overnighted in Copacabana. I loved the rocking motion of the boat out here, but a bunch of people seemed to be succumbing to seasickness. The boats seats were two benches, one along each side of the cabin, and on those we perched. Some people and two yappy dogs were on the deck. Even getting to Copacabana required riding a sort of tiny boat (which was rocky enough that they gave us life jackets) and watching our big bus come across a stretch of water on something resembling Huck Finn’s raft. John’s comment: “There are definitely some vehicles on the lake bottom.”

Taking in the stunning beauty of this place, John said, “Let’s stay here for a month.” It is considered the birthplace of the sun in Incan cosmology, and it feels sacred. It would be amazing to be a writer or a painter and live here for a while. If only. But we are very lucky to be here at all. I was listening to a song: “We’ve traveled so far to be here.” Yes, because we travel our entire lives in a way, don’t you think? John and I visited Lake Titicaca 23 years ago. That was when I fell in love with Bolivia. I’m not sure how much longer this battery will last (it’s John’s old laptop), so I’ll sign off for now. Thank you for sharing our journey with us. Wish you were here, with all of your winter clothes on! Right now I feel toasty warm (at last) and, as I do every day here, so happy to be here.

**************************

John here again. If you’re still reading this shaggy dog – er, shaggy llama – story, I guess apologies for its length are superfluous. It’s late morning of our second day on Isla del Sol, which for the moment is Isla de la Lluvia – Island of Rain. The weather throughout Bolivia has been unusually cold and wet during this entire trip, and so I’m neither surprised nor unhappy about today’s weather – though it may make for a rough ride back on the ferry this afternoon!

We are lodged in a small set of rooms built in the past few years by an enterprising señora named Iola who wanted to divert some of the tide of tourist dollars that has flooded up this hillside lately. This morning we had an interesting chat, which tempered our rosy projections about the pastoral community of this island. Here’s what she told us:

In the old days, when Iola was a girl, there was little to do in the evenings except gather with your family and relations and tell stories, communicating with those closest to you what was really in your heart. There were visitors, but they were few, and given the lack of infrastructure, they tended to be hardy and curious. The islanders had of course always been poor; in fact, Iola’s grandparents were slaves of the local plantation just down the hill from our hotel. But since 1952, slavery has been abolished, and the people were tired of their poverty compared with what they knew of the outside world. In particular, they wanted electricity for their island. It was a twelve-year campaign of petitioning authorities for the extension of high-voltage cables strung from towers straddling the strait between the island and the nearest peninsula.

They finally got their wish in 2000, just as the Millenium broke over the rest of the world. The effect was immediate. As soon as the households got electricity, they started spending their evenings watching TV. Their kids learned more about the outside world than they ever had before. They stopped spending the evenings talking with their elders, they stopped wanting to wear traditional clothes, and they started wanting things that they had never wanted before. What’s more, with electricity came many more tourists, as the island was now able to offer them the accommodations and foods they were used to. The old Hacienda was refurbished as a fancy tour destination. The community became divided between those who wanted to develop tourist facilities as a group, versus those who wanted to build and earn for themselves. A few people started making a lot of money, and others not at all. Some of the new jobs were most suitable for children, such as the young boy who lugged our duffel bag up the steep slope from the wharf to our lodgings. Iola told me that the kids who make money this way lord their wealth over their classmates, and kids who lack this money complain to their parents. And what authority does a father have over a 12-year-old son who makes more than he?

Beret asked Iola whether, on balance, the electricity has been a good thing. She said yes, but not without its drawbacks. And I am thinking the year 2000 was a particularly rough moment in world history to jump from the grassy banks of subsistence agriculture into the deep and swift currents of the service economy, tending to the whims of 20-something backpackers, with their university degrees and gore-tex. We stopped for coca tea at one particularly breathtaking vista overlooking the lake, and in the window of the adjacent pension sat a young gringa fresh from the shower, wrapped only in a towel, sunning herself in full view of whomever passed by. I wondered what conclusions a local boy – or girl – seeing her might draw.

Iola tells us that the community has instituted a 20% tax on all tourism receipts, to be shared among all residents, as a way of evening things out, and she thinks this is a good thing. I wonder whether the island’s traditional, communitarian values might be more adaptive in the 21st Century than the individualist, market-driven phase into which they appeared to be plunging. But for communities, like individuals, it is often hard to skip steps on the staircase of development.

Still, Isla del Sol bit into my heart, leaving an itch more profound than a chuspi bite, and as the ferry took us off into the sunny lake (I am finishing this entry a day after I began it, and the sun returned by lunchtime) I vowed to return, some year, for perhaps a month. Anyone want to come?

— Con mucho cariño,

John & Beret