Zaruma Letter # 2

Queridos amigos y familiares, 24 de junio, 2001

We enjoyed writing our first joint letter and especially enjoyed hearing from some of you in the days that followed. I feel like my senses are sensitively tuned at most times here. When I’m at “zaruma.net,” the sole (and new) internet “cafe” here in Zaruma, which is also a larga distancia telephone outlet with a shortage of telephone lines (one line — so its either phone or internet but not both at once), part of my mind is in the northern hemisphere, and the rest is in the small room, grappling with the stiff keyboard and its differently placed keys, the music and engine sounds drifting in from the street, and whatever else is going on. Two days ago, the Ecuadorean man next to me was weeping copiously into his email, which struck me as brave and open, not what a man from the U.S. would be likely to do in such a public setting.

We enjoyed writing our first joint letter and especially enjoyed hearing from some of you in the days that followed. I feel like my senses are sensitively tuned at most times here. When I’m at “zaruma.net,” the sole (and new) internet “cafe” here in Zaruma, which is also a larga distancia telephone outlet with a shortage of telephone lines (one line — so its either phone or internet but not both at once), part of my mind is in the northern hemisphere, and the rest is in the small room, grappling with the stiff keyboard and its differently placed keys, the music and engine sounds drifting in from the street, and whatever else is going on. Two days ago, the Ecuadorean man next to me was weeping copiously into his email, which struck me as brave and open, not what a man from the U.S. would be likely to do in such a public setting.

Yesterday we had an almost all-day power outage, which pointed out the electricity dependence of our addictions — email, ice cream, warm showers. We have warm water in our shower (if set at very low water pressure) and cold water elsewhere. Cold means cold. We have a three-burner gas stove, which is hard to modulate. It’s a burn and boil kind of stove. We’re enjoying our adventures in food procurement and cooking. I especially love the indoor-outdoor market. Do I miss my fabulous kitchen in Boulder? You bet! But that house feels like someone else’s mansion right now, which it in fact is, as we’ve rented it out and our fish, cat, and my best orchid have all been placed in other homes for the summer.

By late yesterday afternoon, my mother arrived in Zaruma by bus and pickup truck from the coastal city of Guayaquil. She had been on a tour to Machu Picchu, the Galapagos, Quito, and Otavalo. The lovely woman (who is also a nurse at the local hospital) who has been washing our laundry by hand in the cement sink on our balcony-terrace offered to meet my mother at the airport in Guayaquil. Which was a very lucky thing, as it proved harder to get here than any of us expected. Changing buses in Machala, a couple of hours into the journey, required dragging the luggage across several city blocks. We learned that the very next T.A.C. bus from Machala after my mother’s crashed between the small city of Pinas and our city of Zaruma, killing three passengers. I found that pretty unnerving, though when I asked John whether it gave him pause about taking the kids on buses — essentially our only way to go on side trips here — he just shrugged. And I know what he means. You do your best to be safe and then you give over to a kind of fatalism. The drivers in Zaruma are very careful, which they need to be, given the narrowness of the streets and the number of pedestrians, especially children, who are in them at all hours. But elsewhere the passing on blind curves, passing three abreast, passing while the passengers debate about whether they’re better off or worse off if they watch the road, is the norm. We decided to offer an extra dollar to local taxistas if they promise No Unsafe Passing. Ecuador is newly on the dollar — dollarization is generally a destructive thing for Latin American countries — and that makes money dealings easy for us. We can tell when things have sat in stores for a long time because their prices are still marked in sucres, usually to the tune of five or six mystifying digits with a period plunked somewhere in the middle.

We’re two weeks into our ten-week trip and we’re … still happy. We continue to be delighted by this small city and the wonderful people who live here. Word has gotten out about us and why we’re here. It’s said that 3/4 of the families here live off of mining in some way or other. John has all sorts of interview prospects. Last week he interviewed an 84-year-old miner who remembered the old, old days when John’s father was a child. The relationship between Zaruma and mining is not completely obvious because when one is near downtown, as we are, it feels like the city lives off of commerce. But mining is everywhere — any dirt road out of town seems to lead to an artesanal mine. Signs that say “I buy gold” hang from storefronts downtown. Many of the older buildings are wood and there are old-style wooden shutters for many storefronts and swinging saloon doors for saloons. It’s the Ecuadorean West. There’s a store that sells nothing but carbide lanterns. Rubber boots for miners cost $4 and I’m off to buy a pair tomorrow because it looks like we have a mine shoot tomorrow afternoon.

Today we attended a fiesta at a local Catholic school where our neighbor teaches and where we’re going to take Marcus to the pre-kinder to see if he enjoys the preschool scene. John was the Pied Piper of children — at one point, he had about a dozen boys clustered around him and the video camera. We were told my another neighbor that part of the school is actually subsiding and is structurally unsafe because too many mine shafts have been dug into the ground underneath it. Can you imagine? They’re been mining continuously since the mid-16th century here and so they have to go down much deeper than in previous centuries. This is dangerous for a number of reasons, especially bad air and cave-ins. But I bet two hundred years from now it’ll still be going on … somehow.

My friends Lynne and Don were married today in Colorado and I took a walk up above town to commune with their wedding long distance. It was so beautiful at that hour — 5:30 pm — with twilight coming on, the clouds spilling into the valleys between the mountain peaks and lying there in a thick layer, peaks above and peaks below. In the course of my walk, I came upon many gardens — bougainvillea, roses, orange trees, bananas, onion, lettuce, cilantro, mysterious tropical fruits, chickens, dogs, a pig, a gold mine, an improvised cobblestone street (small rocks set into the earth), a house made partly of earth and bamboo, and a girl from the fourth grade class I visited with Paige earlier this week. I love the beauty of this place and I love its sounds — the Andean music that we hear sometimes, the cocks crowing at all hours, the crickets, diesel motors, dogs barking, and hum of human voices.

The ten o’clock siren went off 20 minutes ago, signaling bedtime to all those with timepieces and without. We’re so greedy for our quiet time when the kids are asleep (they’re currently sleeping together across the short axis of a double bed) that we tend to stay up late. The cockroaches tend to creep and skitter in the dark hours, so I slip on my shoes if I get up in the night. Last night we had the most beautiful leaf-mantis creature on our terrace — about four inches long, as green as Ireland in the spring, and shaped like a leaf with skinny legs. It stayed all night and was gone by mid-morning. Paige and her friend Karen have taken to scavenging in the canyon behind the houses — a graveyard of junk and trash and tropical trees and decaying foliage and, oh yeah, all the cockroaches murdered by yours truly.

As you can see, I am not running out of things to say, but I think it’s John’s turn now. We’d like to write a “group” letter a week except for the times when we’re on the road. We’re thinking of trips to Loja/Cuenca in the southern highlands, to Quito/Otavalo in the northern highlands, and to the beach near Machala or Guayaquil. The acute homesickness of Paige and Marcus seems to be subsiding a bit, but still — it has been more intense than I anticipated. Of course, they have a huge language barrier, while John and I are blabbing away in our fractured Spanish. My hubris that our nearly undivided attention would be enough has been punctured, as all hubris ought to be. Now that my mother’s here, we’ll focus on getting some footage shot for the documentary. We miss all of you and hope you’re having a lovely summer. We’ll be at [email protected] while we’re in Ecuador and we welcome all news of you. John and I are happy here and I’ve actually read two books, one set in Sri Lanka and the other set in Nepal-Tibet. Now I’m hanging out with Galileo in the early 17th century. I haven’t started writing poems yet, but I’ve read a bit of Neruda, whose poems I love, and have been keeping a journal…. Be well, everyone.

***

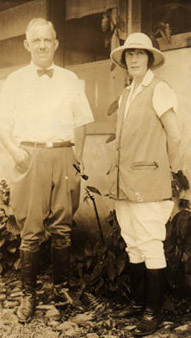

John here. I’m not sure how much there is to add to the above (I’ll claim first dibs on next week’s installment). I guess the main thing is that the fun and of researching our film project has exceeded my high hopes. Last Thursday I went with a 76-year-old neighbor to the town of Portovelo (where the mining operation that my grandfather worked is actually located) and toured the places that show up in our family photos: the giant, cylindrical cyanide tanks used for processing ore; the company store; the camp hospital where my grandmother worked and my father and aunt were born; the gringo social club, with its swimming pool now filled with rubble but the high dive supports still standing; the “casa mirador,” as the house where the family lived was called, set on a bluff above a steep slope with sweeping views of the valley, with the ruins of formal plantings and overgrown, shattered walkways all around. The man who now lives in the downstairs of the gringo social club says he hears ghosts in the billiard room. My image of the place has been so shaped by sepia photos that I was surprised to see it all in tropical green.

And there is a fair feeling of archaeology to the work, as the gringo company left in 1950 and the national enterprise that tried to continue the works failed in 1979. Since then, small-scale miners have tunnelled this way and that with little great success, the ore tailings have been sifted through and the buildings once located on them destroyed, and the company files apparently burned. The headshaft superstructure of the mine, known as “El Castillo,” was knocked down some years ago, to the great distress of the old-timers. And the jungle has worked relentlessly to erase anything that humans have not actively preserved. As a friend once remarked to me, the difference between the first and third worlds is not construction; it’s maintenance.

On the human side much is lost as well. Most of the retirees I am in contact with remember the company in the 40’s, after my grandfather had left. One exception is my neighbor’s 102-year-old mother, who worked as a housemaid for the gringos in the 20’s. She clutched my hand as we talked in place of seeing me, and as I fairly shouted my questions and she keened her replies, I had the feeling of a conversation over short-wave radio with the static drowning out every third word. She was upset by the camera that day and drifted in and out of lucidity, but I hope to get her on tape on a good day before summer’s end.

Some things remain, though. My father’s and aunt’s births remain inscribed in the large folios of the Registro Civil of Zaruma, where even the staff awoke from their bureaucratic lassitude when we found the right hand-written pages from 1918 and 1921. My father’s entry confirms an old family tale, that his middle name was initially “Burr,” until the maiden aunts objected by telegraph from New Jersey that they would nave no great-nephew named after a traitor. So my grandfather relented and changed it to “Bayard.”

Some things remain, though. My father’s and aunt’s births remain inscribed in the large folios of the Registro Civil of Zaruma, where even the staff awoke from their bureaucratic lassitude when we found the right hand-written pages from 1918 and 1921. My father’s entry confirms an old family tale, that his middle name was initially “Burr,” until the maiden aunts objected by telegraph from New Jersey that they would nave no great-nephew named after a traitor. So my grandfather relented and changed it to “Bayard.”

Well, now it’s 11:30 and the kids will be up with the roosters (around here that’s NOT a figure of speech), so I’ll sign off. We’ll try not to be so long-winded next time. Enjoy your northern summers, and be well. XXOO John.

John here. It is remarkably quiet for a Saturday night. There is salsa music pulsing somewhere in the darkness, but too far off to get the melody. It has been over an hour since any M80-sized rockets exploded in our vicinity (though there were twenty or thirty earlier this evening). Only one dog is howling. Nobody is doing any late-night mufflerless transmission testing on the steep grade that winds up past our apartment. And the ten o’clock siren has come and gone, summoning all the Christians to their beds. I may actually sleep tonight.

John here. It is remarkably quiet for a Saturday night. There is salsa music pulsing somewhere in the darkness, but too far off to get the melody. It has been over an hour since any M80-sized rockets exploded in our vicinity (though there were twenty or thirty earlier this evening). Only one dog is howling. Nobody is doing any late-night mufflerless transmission testing on the steep grade that winds up past our apartment. And the ten o’clock siren has come and gone, summoning all the Christians to their beds. I may actually sleep tonight.

And the daily living is full of pleasure. I love the verticality of the environment, present in so many ways: the open-air bus-toboggan ride down the hill to Portovelo (I have become something of a commuter) and the slow grind back up; the switchbacking cobbled trails the miners used to take, now overtaken by ferns and floods and giant spiders; the winding concrete staircases traversing the town instead of sidestreets; the 10-degree temperature difference between Portovelo on the valley floor and Zaruma perched above; and the sweeping, enormous views so ubiquitous that we take them in like air. I, like my father, do adore mountains. And it’s great to discover where he got it.

And the daily living is full of pleasure. I love the verticality of the environment, present in so many ways: the open-air bus-toboggan ride down the hill to Portovelo (I have become something of a commuter) and the slow grind back up; the switchbacking cobbled trails the miners used to take, now overtaken by ferns and floods and giant spiders; the winding concrete staircases traversing the town instead of sidestreets; the 10-degree temperature difference between Portovelo on the valley floor and Zaruma perched above; and the sweeping, enormous views so ubiquitous that we take them in like air. I, like my father, do adore mountains. And it’s great to discover where he got it.